| |

.. |

|

Golput

(Boycott)

|

|

by Paolo B. Maligaya, NAMFREL Senior

Operations Associate |

|

from

NAMFREL Election Monitor Vol.2, No.21

|

|

. |

Like in any other election I observed in

the past, we set out early. With the driver, interpreter, and a

local guide, we hit the road before 6:30am because we wanted to

observe the opening of polls prior to the prescribed start of voting

at 7am. In the Philippines, by 6:30am, the people hired by

candidates to distribute sample ballots and campaign materials

outside polling centers (in complete disregard for election rules)

would already be out in full force. In countries like Nepal and

Afghanistan, the voters, mostly men, would already be gathering

outside polling places with glasses of tea in hand, to await the

start of voting.

We chose to first observe a polling station along the main road;

being close to the market, we

expected a good number of people when polls open. When we arrived at

6:45am, we were surprised

to find that the polling station had not been set up. 7 am. Only a

handful of passers-by to buy bread for

breakfast, and the occasional stray dog. 10 minutes more.

Nothing, nobody.

The idea was to cover a remote area of West Papua on election day.

There were three of us on this

observation mission from the Asian Network for Free Elections

(ANFREL): one was to cover an area

near Sorong, the most populated city in West Papua province; another

was to cover a hot spot area

that saw some election-related violence in the run-up to the July 20

polls; while I was assigned to

cover a tribal area in the Arfak mountains, with the provincial

capital of Manokwari as jump-off point.

The prospect of observing how elections are carried out in

traditional tribal societies was very

intriguing. We were aware of the influence that tribal elders wield

over their tribesmen, including whom

to vote for during elections. How does a democratic exercise such as

an election translate in said

societies? We were not even sure if people in traditional tribal

areas get to have their own choice, or

actually get to go out to vote on election day, and fill up their

ballots individually. We were very curious.

We decided that I would be going to Anggi, an area that would take

almost a full day to reach by

vehicle. The prospect of finding a guesthouse there (!) is close to

nil, so we bought sleeping bags,

raincoats, enough water to last us the entire observation period,

food. We expected to hike, which did

not thrill me at all, but I liked the idea of doing something I

haven't done before in the course of

election observation.

However, there was the matter of the surat jalan, or permission to

travel. In many places in Indonesia,

foreigners especially are required to get the permit from the local

police. Indeed, there was a time

when the whole of Western Papua was off limits to travelers. Permits

are required to go to places that

are considered conflict areas; Anggi apparently is one of those

areas. Or was it really? Many activists

allege that in many areas in Papua, the Indonesian police are

committing human rights violations

against the native Papuans.

We dropped by the local police office, where I was told that

somebody was going to give me the

permit in my hotel later in the day; I was requested to give my

particulars, where I was staying,

including my room number. I did not like the idea of giving the

police even my room number. In 2004,

when I observed the Indonesian presidential elections in Papua, the

hotel manager in Jayapura said

that plainclothes police officers dropped by while I was out to ask

about me and my activities; they

even asked about the driver, his phone number, and my itinerary.

Wisely, the manager said she did not

know. The Indonesian police in Papua are known for closely

monitoring the activities of foreigners,

even Indonesian church people, in suspicion that they are giving

assistance to Papuan organizations

calling for independence. In 2004, I thought such practices were

just remnants of the Suharto era that

the authorities who were so far away from Jakarta still had not

shaken off; now I can't be sure. A

plainclothes police man, whom I would never have mistaken for a

police man because he looked like a twentysomething student from the local college, promptly appeared in

the hotel that afternoon and

asked for a few minutes to chat. Thumbing through my passport, he

noted that I have been to some

conflict areas; sensing where this could be headed, I volunteered

the information that I was in Burma

just for a vacation. Eventually I got my permit.

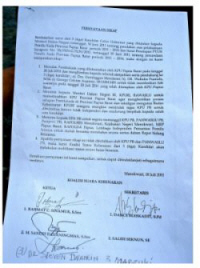

A meeting with the chief of police later in the evening would change

all that. I wanted to give him a

courtesy call before going to Anggi the next day, as is customary

for election observers. The chief of

police said that the situation in Anggi is "hot" right now, and, in

what felt almost like a scolding, strongly

advised me to not go, stressing that if something bad happens to me,

it would be a shame not just for

West Papua (and also for him) but also for the country. Instead,

there were some areas near

Manokwari that I could observe. For some reason, I did not believe

him. As an independent observer, I also did not like that I was

being told where I could and could not do my work, although I knew

that if

it's a question of security, I had to follow. However, it did not

end there. Aside from taking back the

permit already given to me by a subordinate, to be replaced by

another indicating three places where I

am allowed to go, he said I would also be required to sign a waiver

stating to the effect that since I

"insist to observe" despite the warning (which I thought was just

not accurate at all), whatever

happens to me, the police would be free of any responsibility. I

thought this was too much as security

of not just the locals but of everybody in their jurisdiction is

their responsibility, without exception. (I

also could not help but think that a security waiver is a permission

to assault.) After conferring with

colleagues and contacts in the province, I turned in the signed

waiver the following day, but only after

indicating that the waiver would only apply in the three areas

mentioned in the permit. |

.

And that was how I ended up in Ransiki.

It was 8am and no voters had arrived in the lone

polling station in Kampung Ambon. The election

paraphernalia, delivered at 5pm the day before by the

local office of the election commission, had not been

opened because no witnesses from the four candidate

pairs had arrived. The head of the village dropped by

to advise the staff to start the voting once the voters

come in, even if there were no witnesses from the four

candidate pairs for governor. At 8:20, the last of the

polling staff arrived, and the lone witness for the day

(from the incumbents), arrived five minutes later.

Voting started shortly thereafter as voters trickled in;

there were eight who came before we left for the next

polling station. Curiously, all eight voters were transmigrants; no native Papuans had come to vote by

the time we left.

Witnesses of the incumbents were also the only ones

present in the next two polling stations we visited. In

Nuhuwey, we bumped into the head of the district, who had been going

around and visiting polling

stations, asking the poll officers not just to start but to open the

polling stations. According to him, the

head of the village was afraid to open the station because of the

white paper that had been going

around. |

|

Voters would only need to pierce the photo of the

candidate team of their choice. |

|

|

.

Ransiki is a small, rural coastal town three hours from the

provincial capital Manokwari. During World

War II, Ransiki served as a Japanese base camp which, in 1944 alone,

was attacked by US forces

numerous times. Before that, Ransiki was mainly a plantation for

cacao, which to this day occupy a

large part of the town. The people in Ransiki are generally poor,

with agriculture and fishing as the

main source of income. Sparsely populated, the town officially has

only 6,100 voters.

Its relative remoteness did not make it free from the political

controversies surrounding the July 20

West Papua gubernatorial election. A few weeks before the election,

three of the four candidate pairs,

led by the former regent of Manokwari -- Domingus Mandacan -- formed

a coalition to oppose the

candidacies of long-time governor Abraham Atuturi and incumbent vice

governor Rahimin Katjong, on

the grounds that the governor does not satisfy a recent requirement

that candidates have to have

college degrees, and that the vice-governor is not a native Papuan,

even though there is no legal

document that states who may be considered a native Papuan. The

three pairs also refused to

actively campaign, though their billboards were not taken down. When

they were unsuccessful in

blocking the candidacies, they called for the postponement and even

cancellation of the election,

which had already been postponed three times. A few days before July

20, upon their coming back

from Jakarta after one last unsuccessful attempt to lobby for the

postponement of the election, their

supporters descended upon and closed the local parliament building

as well as the office of the

Panwaslu (election supervisory committee) in Manokwari. At this

time, it was reported in the media

that members of the election commission, the Panwaslu, and even the

police started receiving death

threats. The provincial election commission had to leave their

offices out of fear, and had to run the

election from a hotel room in the city. |

|

. |

It was also at this time when a

white paper started circulating,

telling

people to boycott the polls. As an election observer, I always find

it a

problem when candidates ask voters to boycott an election: you have

not

been put in office, yet you are already asking them to give up one

of their

basic rights, which many in the developing world are still

struggling to

demand for themselves. In Indonesia, there is the concept of

“golput”

(“golongan putih” or “the white group”) which roughly means the

exercise

of the right to not vote and remain pure or unstained. Essentially,

it means

to boycott participating in an election or to cast blank votes, a

form of

protest for some. In the past, golput had been a problem in

Indonesian

elections; in 2004, figures showed that the percentage of the voters

who

went golput for whatever reason was higher than the percentage of

those

who voted for the winning party.

However, it may be difficult to gauge whether the case of West Papua

was

a case of golput, or plain intimidation, or something else entirely

in the

context of Papua. The white paper was signed by representatives of

the three candidate pairs, led by Mandacan, an elite of the Arfak tribe. Ransiki is predominantly

Arfak. Twice I saw this paper in the

hands of village chiefs, once in the market, and another time while

we were about to cross a river in a

far-flung area in Ransiki. At both times, the village chiefs told us

casually that they will bring the paper

to their villages for the people's information. The paper called for

the cancellation of the election, the

dissolution of the local election commission for being "not

independent," and threatened mass

mobilization of people if demands are not met. |

|

It was 10:30am and voting in the polling station in Hamawi village

had not started. Only one witness

came, predictably from the incumbents' party. The polling officers

said they had not started because

they were still waiting for information from the city. One of them

was more blunt: he said they were

waiting for instructions from the three candidates. There were also

not much voters to speak of waiting

to vote.

. |

In Kampung Sabri, though the polling station opened at 8:30am,

nobody had voted as of 11am. The

polling officers told us that nobody could vote because no party

witnesses came, even the

incumbents'. They also said that if it's already 1pm (the close of

voting) and nobody had voted, they

will just return all the election paraphernalia untouched. There

were maybe 10 or so people milling

about.

In the official list provided by the election commission,

Sabri supposedly had the highest number of registered

voters among the villages in Ransiki, with 498. However,

we found that difficult to believe: there were only a handful

of small houses in the area. The voters list in West Papua

was based on the records from the civil registrar's office,

given to the provincial election commission in advance for

them to clean, verify and update with regard the names of

those eligible to vote for this year's election. The voters list

had been criticized for containing duplicate names and for

being inflated. Our driver, whose family lives in Ransiki,

said that even if all the pigs and chickens in town were

taken into account, it would still had been difficult to arrive

at the total number of voters in Ransiki as indicated in the

official list. |

|

|

.

No voting was taking place in the next two

villages we visited. While in the other polling stations, the

reasons given for non-conduct of polls were lack of voters, absence

of watchers, and confusion as to whether the election would indeed

push through that day, in the village of Hamor, the polling

officials were more honest: they didn't want to. "Just ask the three

candidates," they said. They added that they will just return the

materials at 1pm. Hamor had 260 registered voters. In Bamaha

village, the polling officers were just as straightforward with us.

314 registered voters. I could not help but think how I would react

if I were one of those voters, and I would not be able to vote

because the polling officers did not want me to. In the Philippines,

there would have been a riot. But this was Papua.

As the voting period winded down, more people had come out to vote,

with some polling stations

indicating that they had more than a hundred voters coming in by

lunchtime. (A fellow observer said

though that there were cases of proxy voting that may not have been

obvious to roving observers like

us, which means that the figures for voters who actually voted may

have been inflated.) In the course

of the day, we learned that no voting took place in many areas of

West Papua, with many villages

rejecting the election paraphernalia when they were delivered, hence

they were brought back unused.

One of the districts that reportedly sent back the materials was

Anggi, the place we originally intended

to observe.

(To be concluded)

Focus on West Papua

Part I - http://bit.ly/okrxOn

Part II - http://bit.ly/psMWRl |

|

|

|

|

| |

.

.

. |

|

| |

| |

|

|